Multi-objective optimisation and Pareto optimality

Often, we are interested in optimising a given problem across multiple objective functions simultaneously.

Multi-objective optimisation is applied in many fields of science and I have most recently applied it in the area of climate science to be able to better constrain end-of-century Australian precipitation change using multiple climate models (manuscript is currently under review).

To better illustrate the idea, let us consider the following scenario. Imagine your goal is to purchase an apartment. On the one hand, your goal is to minimise the cost of the apartment (compared to apartments with the same number of rooms). Cheaper apartments are usually found in suburbs further away from the city centre. On the other hand, you still want to be close to work, which is located in the city centre. One could imagine a third constraint being that we want to minimise traffic noise which can be heard from within the apartment. This is an example of a multi-objective optimisation problem involving three objectives. For this problem, there is no single solution that simultaneously optimises each objective. There is a trade-off between them.

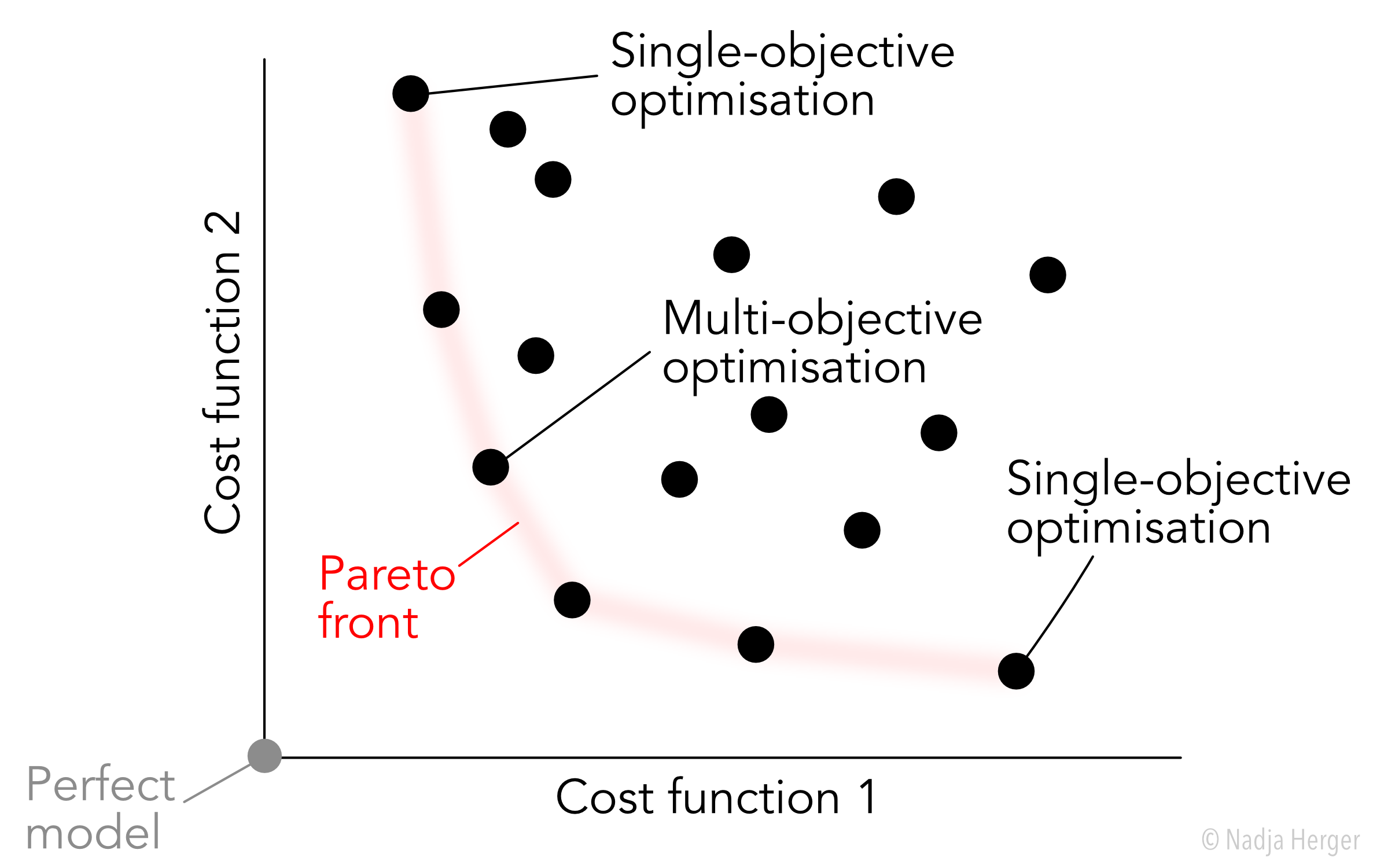

This problem is illustrated in the figure below:

Here, we have two objective functions (e.g. cost of the apartment, and distance from the city centre), both of which we want to minimise. Each dot in this figure represents a separate apartment which is for sale. A “perfect” apartment would be located in the bottom left corner of the plot. Unfortunately, such an apartment does not exist. If we only care about minimising the cost of the apartment, we end up with the apartment in the top left corner. This is the solution to the single-objective optimisation problem. If we on the other hand only care about minimising the distance from the city centre, then we would end up with the apartment in the bottom right corner. However, as we are interested in optimising for both objective functions at the same time, we end up with a range of “good” solutions. With multi-objective optimisation there is no longer a single best solution as we end up with apartments part of the Pareto front (red curve on figure). An apartment is Pareto optimal (and therefore part of the Pareto front), if it is impossible to improve on one of the objective functions without degrading the other one.

It is theoretically possible to simply sum up the individual objective functions by scalarising the individual terms (assigning weights). However, the choice of parameters of the scalarisation is unfortunately often subjective.

You can read up more about methods to find solutions to multi-objective optimisation problems here. I created a sample Python script which finds the Pareto front within a high-dimensional space on my GitHub repo.

- Lessons learned in AI Governance

- My Journey from Climate Science into Responsible AI

- Photo Clustering

- Multi-objective optimisation and Pareto optimality

- Out-of-Sample Testing in Climate Science

- Climate Change Scarf

- Hackathon

- Combinatorial optimisation with Gurobi

- Visualising the model space with unsupervised learning

- Setting up Jekyll on GitHub Pages